Religion

Religion

Christianity

Christianity

Christianity

Christianity

Davis Community CHurch

Davis Community CHurch

Don's Home

Religion

Religion

Christianity

Christianity

Christianity

Christianity

Davis Community CHurch

Davis Community CHurch

|

The marches were organized by nonviolent activists to demonstrate the desire of African-American citizens to exercise their constitutional right to vote.

The first march which took place on March 7, 1965, was ended by state troopers and county possemen, who charged on about 600 unarmed protesters with batons and tear gas after they crossed the Edmund Pettus Bridge in the direction of Montgomery. The event became known as Bloody Sunday.

The second march took place two days later but King cut it short as a federal court issued a temporary injunction against further marches.

The third march, which started on March 21, was escorted by the Alabama National Guard under federal control, the FBI and federal marshals (segregationist Governor George Wallace refused to protect the protesters). Thousands of marchers averaged 10 mi (16 km) a day along U.S. Route 80 (US 80), reaching Montgomery on March 24. The following day, 25,000 people staged a demonstration on the steps of the Alabama State Capitol.

Key Figures:

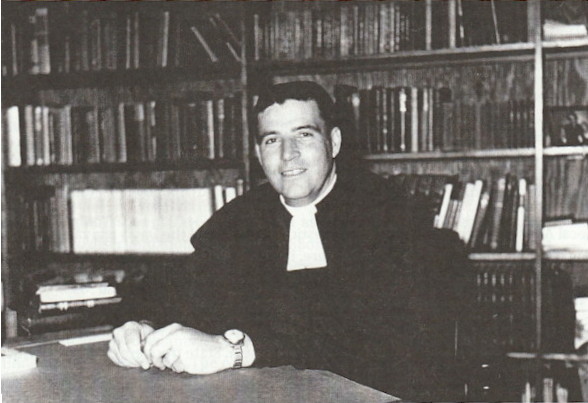

DCC Pastor, Dewey Proett, talked about it in a sermon.

A Pastor Marches for Civil Rights.

I did not want to go! I fett deeply sensitive to the members of the Church who for reasons of place of birth or upbringing could not sympathize with the trip and who would be deeply hurt by my participation...but, quite unexpectedly, was the overwhelming support that came from members who, up to now had not revealed such a tremendous concern for the world... many have since told me that this has now strengthened the church. They thought people had the false image of Community Church being that large, comfortable church at 4th and C that would not be moved to active participation in the cares of others. But when the Pastor went - the image was changed.

--Rev. Dewey Proett sermon notes, April 1965

In early '1,965, racial tensions were running high in the South. Thwarted in their efforts to register voters, civil rights leaders had planned a march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama. This "Bloody Sunday" incident ended with the brutal suppression of peaceful protestors by state police.

In response, a message went out from Martin Luther King, fr., for clergy and others to join in a march of solidarity in Alabama. Rev. Dwayne 'Dewey' Proett, pastor of Davis Community Church, heard the call and struggled with his decision. There was obvious risk involved--a minister from Boston recently had been murdered in Selma. But Dewey was particularly concerned about the effect on his congregation. Would his journey be divisive, damaging the trust that church members had placed in him?

After earnest discussion with church leaders, the pastor made his decision to join others on the trip. The 35 diverse participants included Terry Turner, a young African- American post-doctoral researcher at UC Davis. Another was A. Karasaki Ota, a fapanese-American whose relatives had been interned during World War II. The clergy, educators, and other men and women who joined the group agreed to a pledge of nonviolence on the journey.

In a sermon following the march, Rev. Proett described the friendships forged on the long ride, with sharing of food and ideas. As the bus entered the Deep South, passing Confederate flags along the road, the interracial group encountered the challenge of dining at segregated lunch counters. At one stop, they succeeded in shifting two tables together at the demarcation line between black and white patrons, thus avoiding separation.

A local African-American church enthusiastically welcomed the Davis arrivals, serving them fried chicken and other Southern fare. In return, Dewey used his musical talents to play gospel hymns. The Davis group slept in the sanctuary, with volunteers staying up all night to provide security outside the church.

The Davis group participated in the final miles of the Selma-to-Montgomery march. White supremacists shouted insults and spat on them. State troopers cruised by with Confederate flags on their bumpers.z Fortunately, Federalized National Guardsmen sent by the Federal government were on hand to provide protection for the marchers, and helicopters buzzed overhead. As they reached the state capital, the march had swelled to 25,000.

The march itself was exhausting and exhilarating, frightening and triumphont. Anyone who has lived through more than forty summers to begin a trip on a Greyhound bus right after three sentices of worship, with added emotions ond conflicts, stay on the bus for approximately sixty hours, and then walk fiwelve or more miles In sun and rain, would know what I mean when I say Itwas exhausting.The highlight of the event was an inspiring speech by Martin Luther King, Jr. Despite pouring rain, the marchers then were treated to an outdoor concert featuring loanBaez, Pete Seeger, Harry Belafonte, and other notables.

The Selma march participants went on to play leading roles in the community. Richard Holdstock was elected to the Davis City Council in the 1970s. Rev. Philip Walker later served as head of Yolo County health services. Terry Turner went on to teach for thirty- five years as a professor of art and humanities at Woodland Community College. And Rev. Dewey Proett returned to continue serving as pastor at Davis Community Church untll1,97 4, providing a model of courage for his congregation.

In2013, President Barack Obama joined Rep. fohn Lewis and many others to commemorate the fiftieth anniversary of Bloody Sunday. In a special gesture of solidarity, he held the hand of Amelia Boynton Robinson, who had been beaten during the march. Robinson went on to play a leadership role in the civil rights movement.

While civil rights issues of the era often were associated with the Deep South, Davis was not immune to discrimination. In some neighborhoods, property deeds contained restrictive covenants, prohibiting sales of homes to any "non-Caucasian." As the university grew, diverse educators recruited to the campus were confronted with this dilemma, blocked from residing in sections of the town.

Since that era, these covenants have been invalidated by the courts, but still exist as a reminder of earlier prejudice. The community and DCC have been striving to become more inclusive and diverse, finding inspiration in the examples of Rev. Dewey Proett and Martin Luther King, Jr.